Seasons

Passing Time in Persona 4's Tourist Town

I grew up going to vacation towns on the coast in the off-season. Locked-up boat sheds, storm-clouded beaches, and glasslike seas decorate some of my happiest memories. There’s pleasure in being an off-season tourist. Summer tourists go without artifice, as themselves; in winter, tourists are undercover as locals. Even though you’re not from a place, for a while, you can pretend you are.

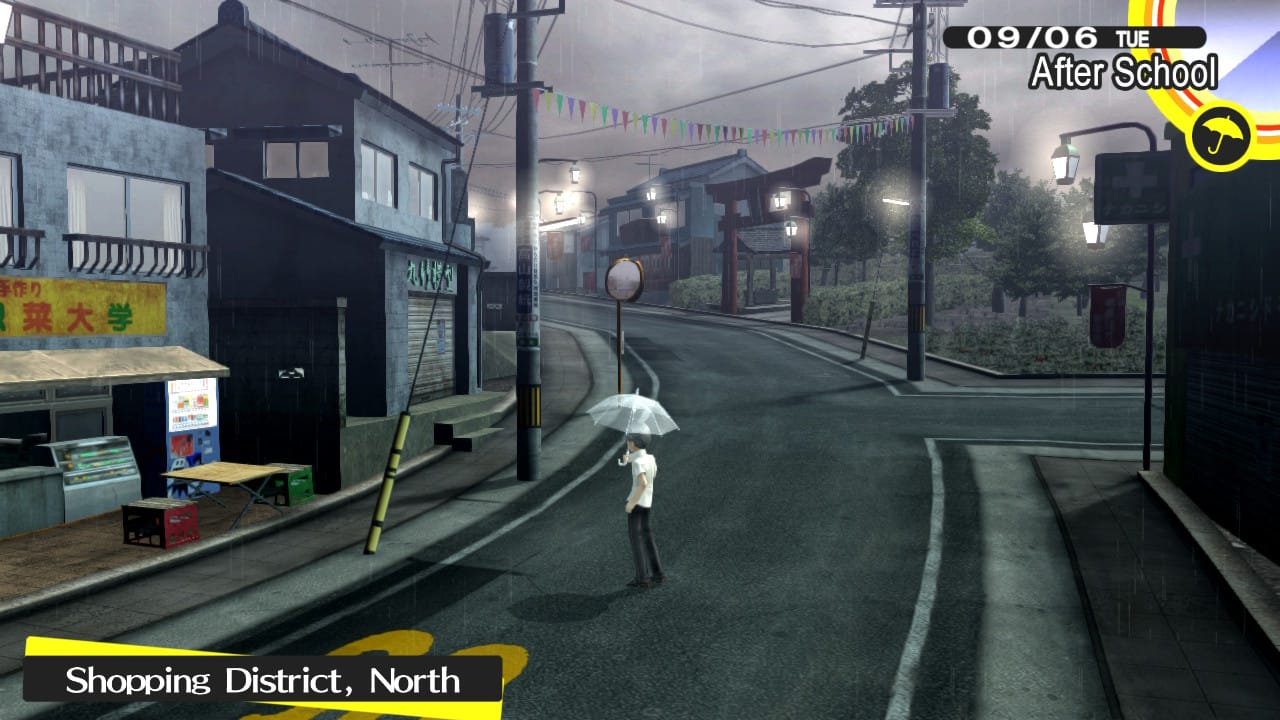

Persona 4’s Inaba doesn’t have an off-season exactly, because it’s always off-season. A small town plagued by mysterious fog and serial murders – the two, it turns out, connected – Inaba’s options for fun are hanging out at the megastore and fishing. You’re a visitor staying with family, but at the same time you get to be from here: you go to school for a whole year. You’re neither a delinquent nor an outcast, but a well-liked kid who only needs to schmooze a little to really be popular. The town’s annual events, spaced out like diamonds on a crown, show you an aspect of rural beauty in each seasonal facet.

Yet like a real vacation town, Inaba reserves itself from you, making you work to really see it. It changes with the seasons and adds and removes opportunities as they progress, giving and taking away events, quests, connections, and even clues in the murder case. Becoming familiar with Inaba through its many changes ends up being an important part of solving its mystery. That hard-won familiarity also teaches the player that careful attention to detail is important and that how you use your limited time matters ‒ a theme of the Persona series as a whole.

Persona 4 is now (until its remake comes out, anyway) the oldest game in the main Persona series and the least convenient to play. It lacks many of the concessions Persona 5 and Persona 3 Reload make for player ease. For example, simple actions like persona fusion are more inconsistent, and side quests depend on unpredictable RNG. Persona 4 also blocks out large parts of your summer and winter break for The Plot, leaving you scrambling to kiss your girlfriend or force the relationship with a Rank 6 connection before time is up.