Skyboxes

The Rotting Pizza of Final Fantasy 7

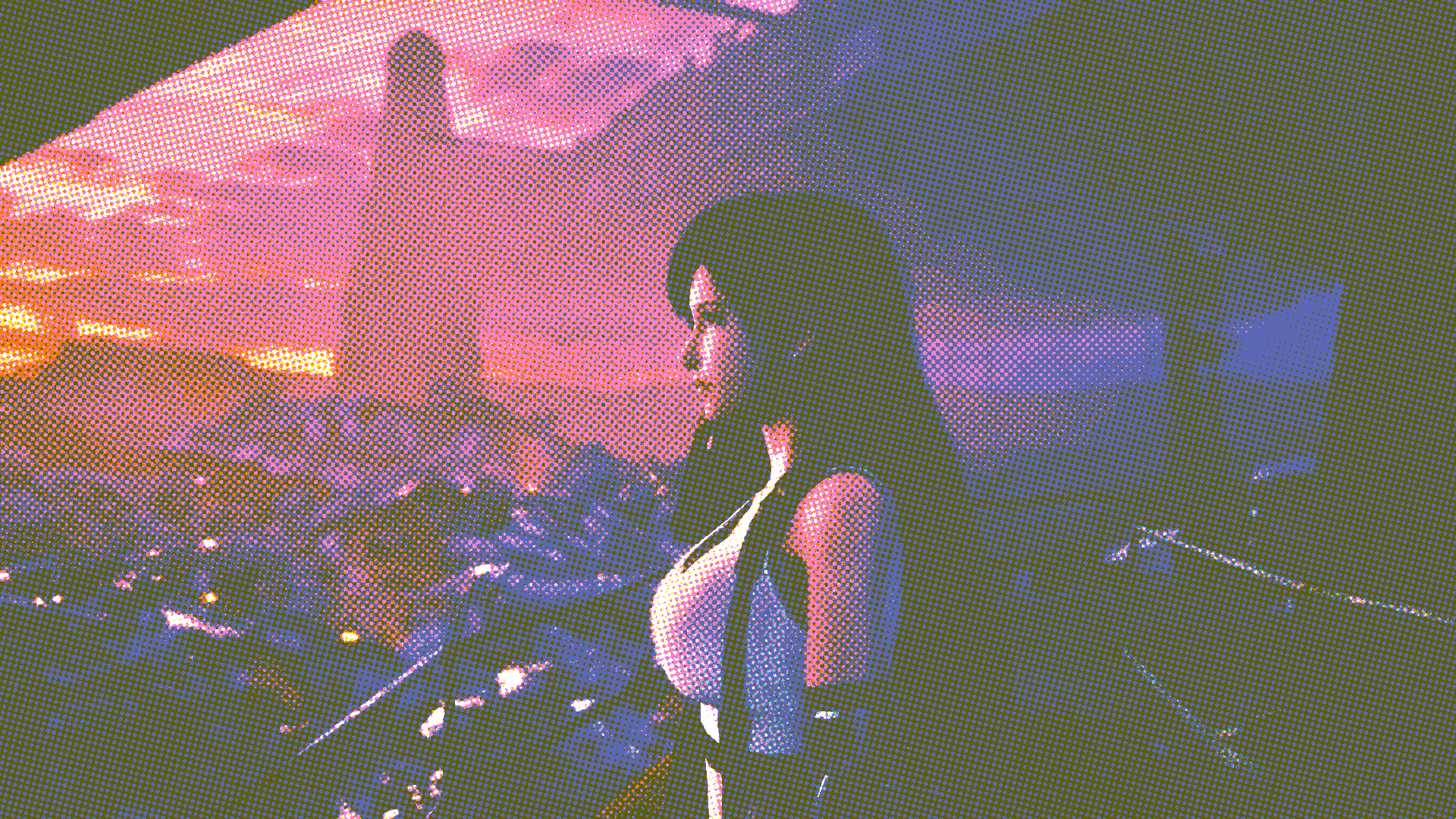

After a treacherous, stomach-churning climb that takes me through the ruins of a church up into its dilapidated spire, remnants of a city surround me. I look up at the slice of the circular structure where these buildings fell from, gazing up from under the rotting pizza. Tracing the intricate pipework, you can see how the organs of the city collapsed into the slums below: even from atop a roof, with winds blowing precariously, I am miles below Midgar. The sheer scale is overwhelming, the detail and fidelity of the world captivating.

At this point I’m about 10-20 hours into Final Fantasy 7 Remake. The game has taken me on a journey through incredibly modelled environments, places familiar, gloriously elaborated on and unfurled with unbelievable technical mastery. However, the most breathtaking view is now presented to me, the skybox of the city ‒ ambitiously rendered in excruciating detail. I can’t take it all in at once: it looks like a frame from Akira or Ghost in the Shell, and echoes the Architectural forms of Expo Osaka 1970’s Space Frame Inhabitable roofing systems. It makes me wonder, would this level of worldbuilding and detail exist without having the ‘prototype’ of the original PS1 game?

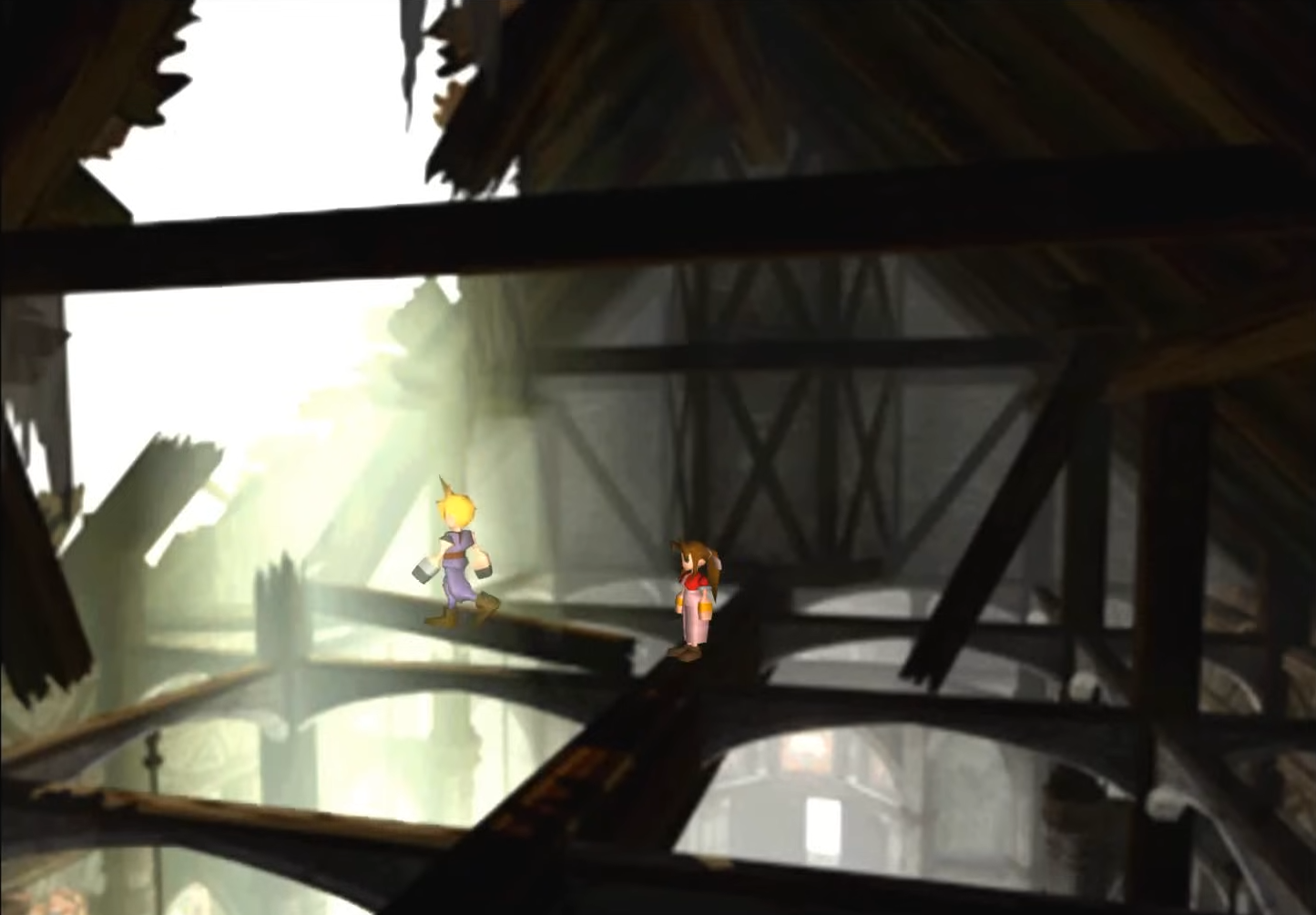

In older PS1 JRPGs, there is a constant interplay of different scales of fidelity in representing environments and characters. In Final Fantasy 7, you have the iconic cubic characters of the city exploration set over pre-rendered backgrounds, the higher resolution character models and smaller environs of combat arenas, dazzling (well, don’t look too closely now) pre-rendered cutscenes and fully 3D world maps.

This is a typical composition of SquareSoft JRPGs of the era, and this particular configuration lent itself to the kind of storytelling typical in 1997: world-saving, sometimes intergalactic, godslaying epics where the possibility spaces of these worlds were infinite. In Xenogears (originally slated to be Final Fantasy 7) this play of scale was pushed to new levels with the use of mechs pulling cameras out even further, and rotating cameras making environments even more layered and three-dimensional, with characters instead taking the 2D approach ‒ inverting the approach of FF7.

The pre-rendered environmental approach meant that artists could build the image of the environments from one perspective, knowing precisely the angle of the camera and distance objects would be shown from ‒ utilising the blurring effect of CRTs to blend the 3D characters with the low resolution imagery. Even having a rotating camera like in Xenogears creates difficult angles of the environment, with awkward views obscuring navigation paths and characters, and with a reduced ability to create asset variation and details within environments.

This interplay of pre-rendered environments ‒ being able to go from intimately zoomed-in shots inside elevators and train carts to zoomed-out world views ‒ encouraged the worlds of these JRPGs to contain both fragments of minutia and awe-invoking scale. Seeing the smaller spaces, cities and then open world leads one to fantasise: what other places could be out there in this vast landscape?

The last 10 years of game releases have often involved large open worlds, where everything you see is ‘real’ ‒ that mountain over there? You can climb it! This is an incredibly powerful tool in itself, drawing players to a point of interest in a landscape and allowing them to discover what is or isn’t there ‒ something that captivated me enough to spend several years of my life dedicated to making a game that does just that. However, for all the incredible moments of ‘that mountain over there’, seeing the skybox of Final Fantasy 7 Remake made me think back to the value of occasionally denying the player ‒ saying, no, that place exists, but it is not for you.

Final Fantasy 7 Remake is a pretty linear game: it occasionally uses very limited hub and spoke design, but the city is mostly a construction of ‘corridors’ of space. In some ways, this is very similar in construction to the original game, with small crawl spaces providing loading opportunities between areas. These interstitials are not only beneficial technically, but allow the city itself to be designed without being overly concerned with coherence. The image of the city is constructed in the player’s mind: how particular spaces are connected whether by corridors of rubble or obfuscating elevators is crucial to maintaining this illusion. It is a spatial translation of the concept of jump cuts, essentially. Where the original game did not shy from a fade to black, a dramatic camera angle alteration and occasional scale shift, the modern interpretation aggressively avoids this. The designers are desperate to create continuity of space, even if it means 30 seconds of crawling through a hole to do so.

Perhaps because of the technical abilities afforded to us as modern game developers ‒ with the draw of fully controllable 3D cameras and increased resolution ‒ developers cannot afford to create worlds with the same scale and detail. Even the FF7 Remake had to be split across three games. The pre-rendered skybox is a big commitment, as it ties you to a specific perspective and view of the world. Players cannot ‘enter’ the skybox, but instead must dream of a world beyond its borders. In an age of AAAA spending, with the frequency of game development becoming increasingly long and fidelity prompting the desire to show as much as possible, technological developments are paradoxically not ‘enabling’ developers, but instead allowing us to over-detail. In some ways, this excessive detailing prevents the player from being able to use their imagination and world-build in their mind. Good design comes from limitations, after all.

The PS1 FF7 team had to construct a world that relied on the player's willing participation, asking them to engage their imagination and creativity. The only way for FF7 Remake to live up to the scale and magnificence of the constructed world of the player, therefore, was to utilise this same technique. Instead of making a fully open-world Midgar that Cloud could freely explore and drive around, it was more economical and more effective for the developers of Remake to use one of the oldest tools available to 3D developers: the skybox.

If you enjoyed this slice of FF7 analysis and are hungry for more, sign up for the Eteo Archetypes newsletter for weekly articles, plus important updates from Eteo games studio.

You can also join the Eteo Discord server to discuss this piece and other Archetypes articles in a friendly and thoughtful environment.