Skyboxes

Designing Oppression in the Skies of Half-Life 2

From The Children of Men and The Pianist to Let The Right One In and No Country For Old Men, gray skies have long served cinema when it has aimed to evoke melancholy. Whenever a director has wanted to foreshadow an impending storm or ‒ at the very least avoid the cheerfulness of a blue sunny day ‒ gray skies have been used to set the mood. The desaturated colors of a sunless day make scenes feel subdued and colder, while the diffused lighting softens shadows to create a muted, even eerie atmosphere ‒ simultaneously conveying a sense of realism and isolation.

When the late art director Viktor Antonov decided to showcase Half-Life 2's City 17 under the light of a barely visible sun, it could have merely been a case of video games borrowing the visual language of cinema. Antonov, however, was never one to simply lift obvious recipes to construct places ‒ let alone when it came to the masterpiece he was instrumental in shaping. Overcast cinematography must have been an inspiration, yes, but the game certainly looked further than that.

Antonov perceived cities as characters, and characters come with distinct physiognomies sculpted by obvious and non-obvious elements, the combination of which can make them memorable. Less exotic than his work on urban settings such as Dishonored’s Dunwall, City 17 would be a place of strong sci-fi undertones meant to feel different yet real, and its skies were envisioned as narrative and atmospheric pillars of worldbuilding, there to simultaneously immerse and reinforce themes.

The skybox itself was never a Half-Life 2 innovation. Ever since the 1990s and Doom it had been an important storytelling and artistic tool, crucial in implying worlds much larger than the ones actually rendered. At its simplest, a skybox is a textured cube ‒ or sphere ‒ simulating the sky or other distant backgrounds surrounding the playspace. It provides the game with a horizon that moves along with the player, and serves as a surface on which far-off scenery is projected.

From the player's perspective, a skybox mainly comprises the limits of what they see; of all those elements implying a wider world that are too far to interact with. This more holistic view very much involves lighting, itself a fundamental component of all games. After all, skyboxes determine the time of day and the weather, and so tell us how to light levels, and how to render shadows and colours. Change the sky and everything needs to adapt to it.

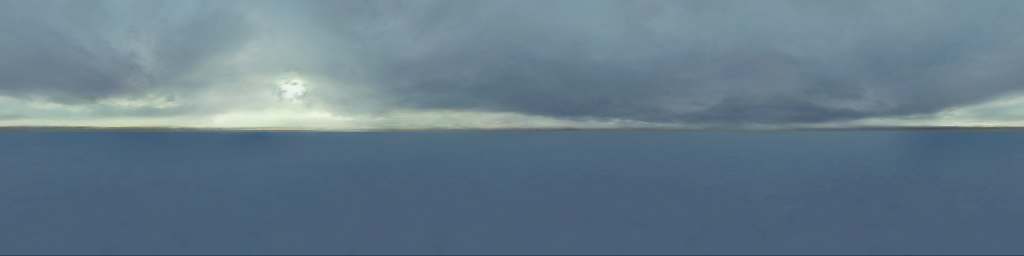

Valve was determined to use Half Life 2’s skybox to give audiences a sense of vastness and realism. Artistry was certainly part of this, but so was its technical foundation. These skyboxes were groundbreaking, as Valve combined textures with small-scale, low-poly models placed inside them to create realistic distant objects. The skybox itself was detailed, animated, and seamlessly integrated into the game's lighting system, allowing for environmental changes to dynamically interact with how elements were lit.

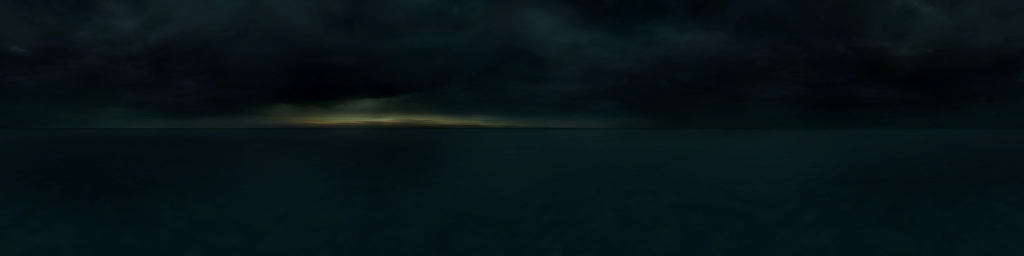

Regulating lighting served as a tool to establish mood and set the emotional tone. Outside City 17, for example, the skybox changes to showcase the open skies and distant oceans of Highway 17, revealing a vast horizon with rolling hills and abandoned buildings. Then, during the mid-game and in places like Nova Prospekt, the sky darkens emphatically and the lighting becomes starker, signalling a rise in tension and danger; in Ravenholm night falls to set up horror. Throughout the game the skybox is there, influencing player emotions and establishing a specific sense of place. It is never as important an actor as it is in City 17, where it serves as a main axis of the city’s image: there to conjure a complex but distinct sci-fi-romantic-melancholy atmosphere with touches of horror.

Antonov, who as a kid explored the forgotten nooks and crannies of his hometown of Sofia, often talked about wanting to reproduce the sense of being in a new, mysterious place. A place that felt believable and unique, and, in the case of Half-Life 2, a place whose spaces would simultaneously serve the needs of the gameplay. While level design handled the latter, to achieve the sense of reality Antonov borrowed and interpreted elements of reality. Sofia, which he already deeply knew and of which he had hundreds of photos taken, served as a brilliant source of inspiration and a starting point. To this, he mixed in elements from Belgrade and St. Petersburg, and a replica of Budapest’s Nyugati station, taking advantage of the fact that Eastern Europe was almost completely unexplored by gaming.

Antonov’s references were thus simultaneously familiar and unknown, and just as successful as Valve’s choice to start the game in City 17. This city, like all cities in fiction, serves as a concise yet rich embodiment of the game's universe by being dense, complex and teeming with NPCs. It can quickly and clearly convey maximum information within a given, condensed area. In a matter of minutes players realise that this is a dystopian city under occupation, but also home to an armed resistance.

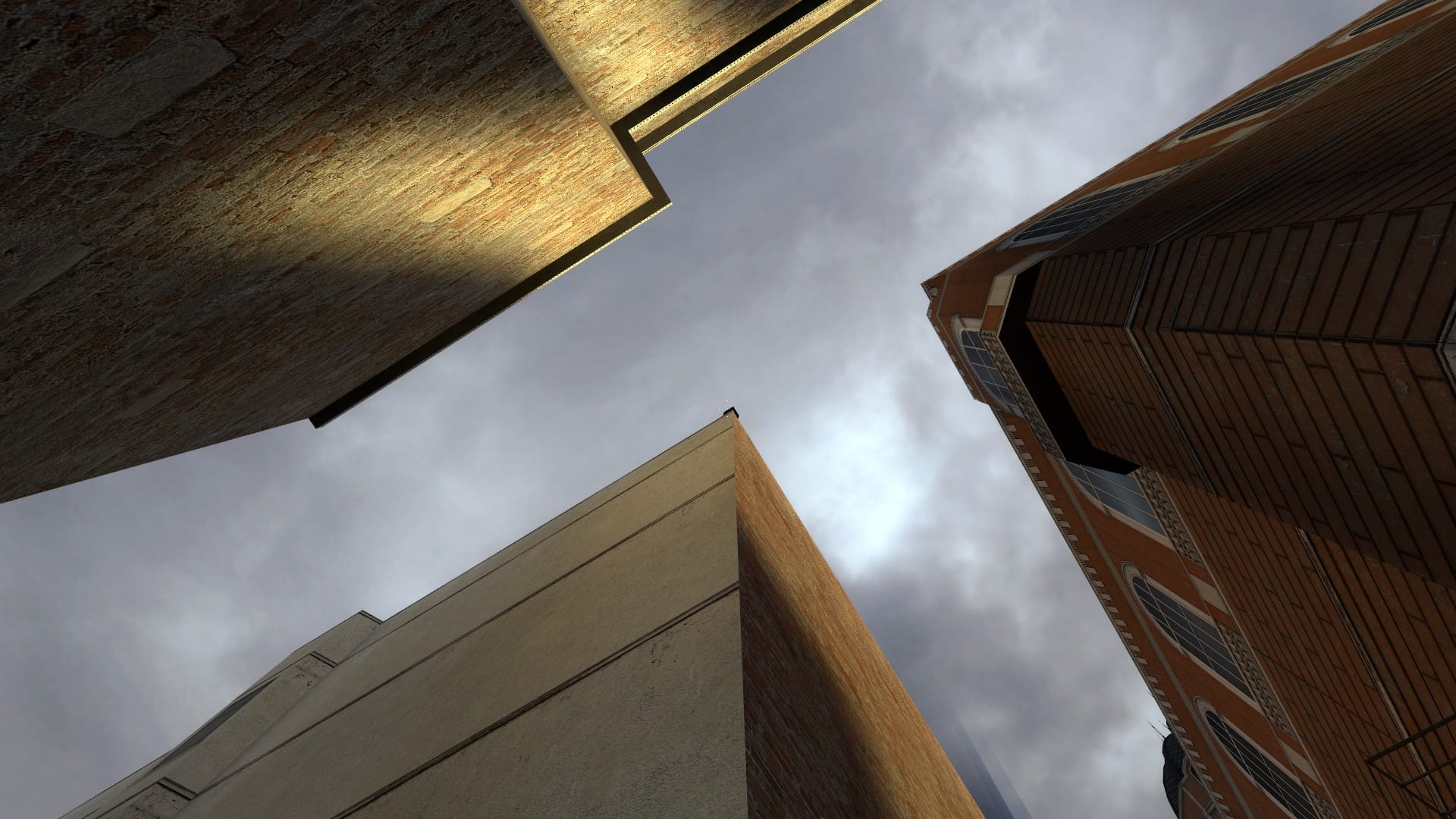

Surrounded by Bulgarian-inspired courtyards, central European grids, and the layered architectural diversity required to imply an actual historical past, looms the Citadel tower. It is a powerful symbol of alien oppression, and a landmark dominating the urban tissue, rising above the gray, industrial skyline. This omnipresent alien-brutalist structure is the centerpiece of the skybox, always there to oppress players and remind them they were never far from the Combine’s reach. As with all successful landmarks, the Citadel benefits from the negative space surrounding it. It stands out against the sky drawing the eye, constantly reminding the audience of the world’s scale, as well as their ultimate goal and enemy.

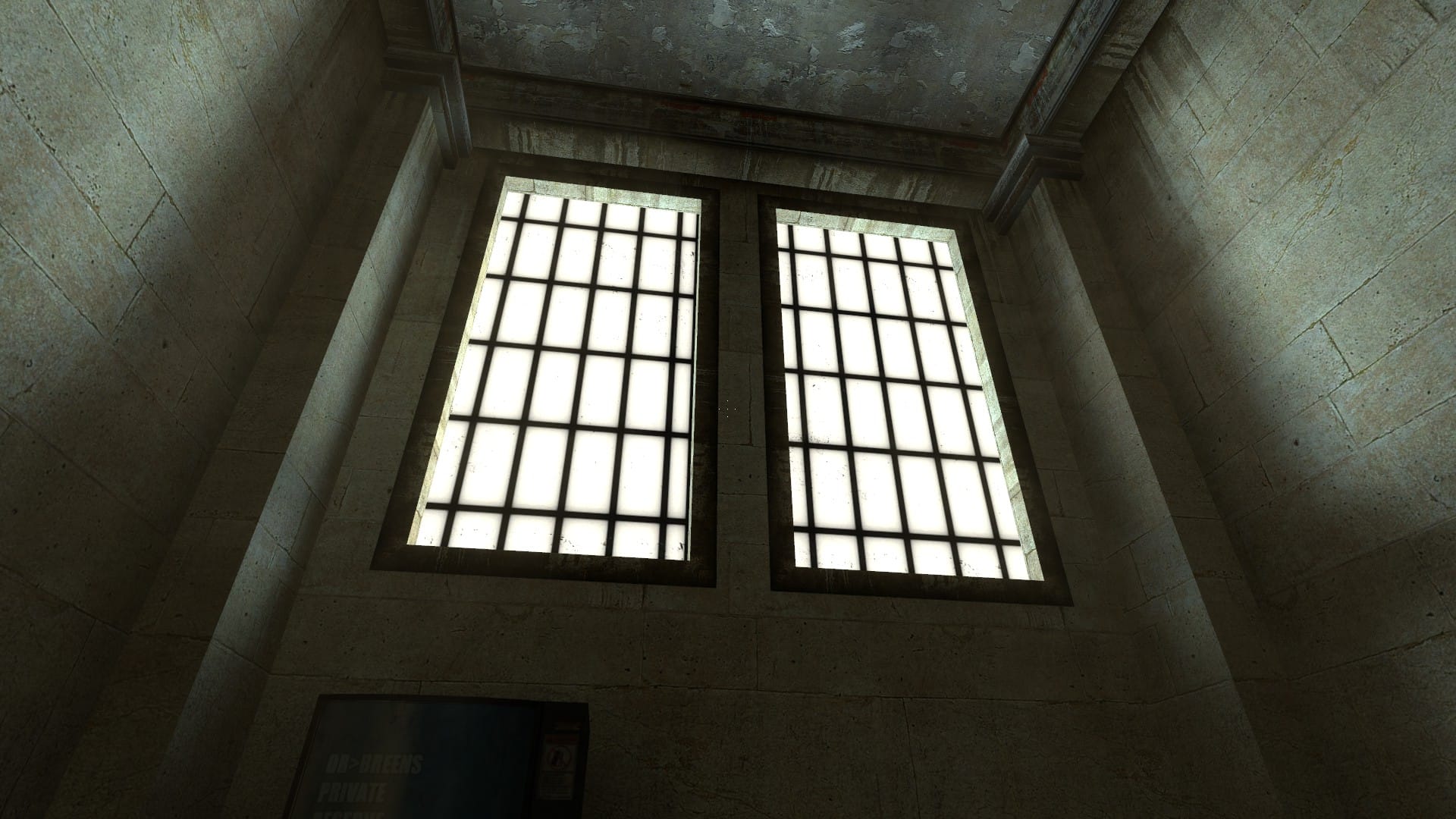

Interestingly, however, City 17’s impressive skybox is introduced gradually. Players are brought into the city via train – a very effective and familiar way of entering any new town, but also a direct reference to the introduction of Half-Life 1 – making the sky difficult to directly observe from within. Its colours are reflected in the palette choices, but to directly see the skybox players have to put in the effort and try to look from the train’s window before entering the main station; only to see a thin ribbon of sky. Following the train ride, audiences have to wait even longer before being exposed to open air. The enclosed spaces of the station feature nothing but dull windows, only allowing the quality of the world’s light to be sensed and the skybox itself to be foreshadowed.

It is only after exiting the station that players are finally exposed to the beautiful, overcast sky of City 17, which somehow makes exteriors feel as oppressive as interiors. The feeling is supported by the evident hopelessness of the observed new normality. The signs of occupation in the city are everywhere from the architectural contrasts of Combine and human architecture, to the occupation’s police checkpoints. The lack of joy is further emphasized by the washed-out sky, and diffused, pale lighting. This lack of warm light combined with the muted architecture and anemic vegetation contributes to a lifeless, almost sterile and alien setting.

Antonov actually spent a lot of time researching the game's light. He measured the sunbeam angles and humidity levels across cities in northern and eastern Europe, and determined that the atmosphere he was aiming for demanded an angle of up to 45 degrees. The resulting long shadows are made softer by the clouded skybox, adding a touch of autumn nostalgia to the proceedings. The harshness of winter would have probably been too hostile, whereas a September sky does indeed fit a more nuanced, more tragic world better.

Of course, there are neither vibrant blue skies nor golden sunsets here. Everything is cast in a dull, gray and occasionally yellowish haze suggesting something is off with the atmosphere. On the other hand, the constant lack of bright light from a sky without warmth makes the city’s emptiness almost unbearable. Direct sunlight is missing too, and in the few instances when the sun can be glimpsed behind a thin cloud, it is dull and impressively non-blinding. Patches of clear sky are rare, but so is the lack of motion. Though the lighting remains mostly flat and the sun unmoving, looking up reveals flocks of birds, threatening (flying) city scanners, and the occasional attack chopper.

Environmental storytelling and atmosphere-building have rarely reached the heights of Half-Life 2. City 17’s sky remains, in my eyes, the most memorable in gaming, despite lacking extraordinary elements or vibrant colours. It is heavy and oppressive and something I learnt to long for both while playing through the games’ enclosed and underground sections, and when merely thinking about it. And though I can always revisit it, what we will all forever miss is the brilliance of Viktor Antonov. His untimely death has left an irreplaceable gap both in the world of video games, and in the lives of all who loved him.

If you enjoyed this piece and want further insightful articles on video game design, sign up for the Eteo Archetypes newsletter. You'll get the weekly Archetypes article delivered straight to your inbox, along with any important announcements from Eteo games studio.

You can also join the Eteo Discord server to discuss this piece and other Archetypes articles in a friendly and thoughtful environment.